A Systematic Process for Feature Selection, Feature Dropping, and Algorithmic Self-Selection in Iterative Machine Learning Development

Feature selection is the most consequential and least disciplined step in the machine learning pipeline. Despite decades of research into individual selection techniques, practitioners lack a cohesive, end-to-end process that integrates domain expertise, statistical methods, and algorithmic self-selection into a repeatable workflow suitable for production ML systems.

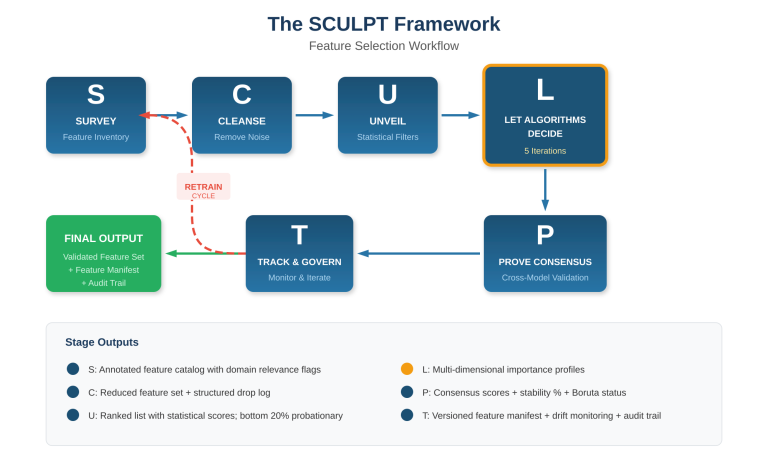

This article introduces SCULPT—a six-stage framework (Survey, Cleanse, Unveil, Let algorithms decide, Prove consensus, Track and govern) that provides a structured decision workflow for feature selection and dropping across the full model development lifecycle. SCULPT is distinguished by three characteristics: it treats feature selection as a progressive, iterative process rather than a one-time step; it explicitly leverages the inherent feature selection mechanisms built into ML algorithms during training; and it embeds governance and auditability as first-class requirements rather than afterthoughts.

The framework is designed for practitioners building supervised learning systems on tabular data, and is particularly applicable to regulated environments (healthcare, financial services, pharmaceutical development) where feature decisions must be documented, defensible, and traceable.

The Gap Between Feature Selection Theory and Practice

The academic literature on feature selection is extensive. Filter methods, wrapper methods, and embedded methods are well-cataloged, with hundreds of papers comparing their performance on benchmark datasets. What the literature does not provide—and what practitioners urgently need—is a workflow. A sequential, stage-gated process that tells you not just what the tools are, but when to use each one, in what order, how they interact, and how to validate that the result is stable and defensible.

In practice, most data science teams apply feature selection as a cursory step: compute a correlation matrix, apply a variance threshold, perhaps run recursive feature elimination, and proceed to model training. The result is a feature set that has been examined by one method, at one point in time, without validation for stability, without cross-model confirmation, and without any documentation of what was dropped and why.

Three consequences follow predictably. First, models are bloated with noise features that reduce generalization and increase inference cost. Second, feature importance is model-specific rather than model-agnostic, meaning the feature set is optimized for one algorithm and may perform poorly if the algorithm changes. Third, there is no audit trail—when a regulator, auditor, or business stakeholder asks why a particular variable is or is not in the model, there is no documented answer.

SCULPT addresses all three problems through a structured, six-stage methodology.

The SCULPT Framework: Overview

SCULPT is an acronym for six stages that are executed sequentially, with the output of each stage feeding the next. The final stage loops back into the first on every model retrain cycle, making the framework inherently iterative.

Figure 1: The SCULPT Framework — Six stages with iterative retrain cycle

Stages 1–3: From Raw Features to Statistical Relevance

The first three stages of SCULPT are preparatory. They transform a raw, unexamined feature space into a statistically profiled, noise-reduced candidate set ready for algorithmic evaluation.

Stage 1: Survey the Feature Landscape

Every feature is cataloged by data type (continuous, categorical, ordinal, binary, derived), source system, distribution characteristics (cardinality, skewness, missing value percentage), and known relationships to other features. Domain experts annotate the catalog with relevance assessments and flag features that are irrelevant by construction—patient identifiers, row indices, fields collected after the prediction event (leakage candidates).

This is not a formality. Domain knowledge is the single most efficient feature filter available. A clinician reviewing a drug safety dataset can identify leakage features in minutes that would take an automated pipeline hours to detect—or miss entirely. The output is an annotated feature catalog that serves as the baseline document for all subsequent decisions.

Stage 2: Cleanse Obvious Noise

Four categories of features are removed deterministically. Zero-variance and near-zero-variance features (those with 95%+ of values at a single level) carry insufficient information for any model. Highly correlated duplicates (Pearson r > 0.95) introduce multicollinearity without adding signal; one is kept based on domain preference, data completeness, or source reliability. Data leakage features—any variable encoding information unavailable at prediction time—are the most dangerous class and require both automated detection (target correlation > 0.99) and manual domain review. High-cardinality identifiers enable memorization rather than generalization.

Critically, features with moderate correlation (0.7–0.95) or substantial missing values (20–50%) are flagged but not dropped. They proceed as candidates subject to elevated scrutiny in later stages. Every removal is logged in a structured drop log with the feature name, reason, threshold, and date.

Stage 3: Unveil Statistical Relevance

Multiple complementary filter methods are applied in combination: mutual information (captures nonlinear dependencies), chi-square tests (categorical features vs. categorical targets), ANOVA F-statistics (continuous features vs. categorical targets), and Spearman rank correlation (monotonic relationships). Features scoring in the bottom 20% across all applied filters are designated probationary—they proceed to Stage 4 but must earn their survival through algorithmic validation.

The essential limitation of this stage is that filter methods evaluate features independently. They cannot detect interaction effects where individually weak features combine to produce strong predictive signal. This limitation is specifically addressed in the next stage.

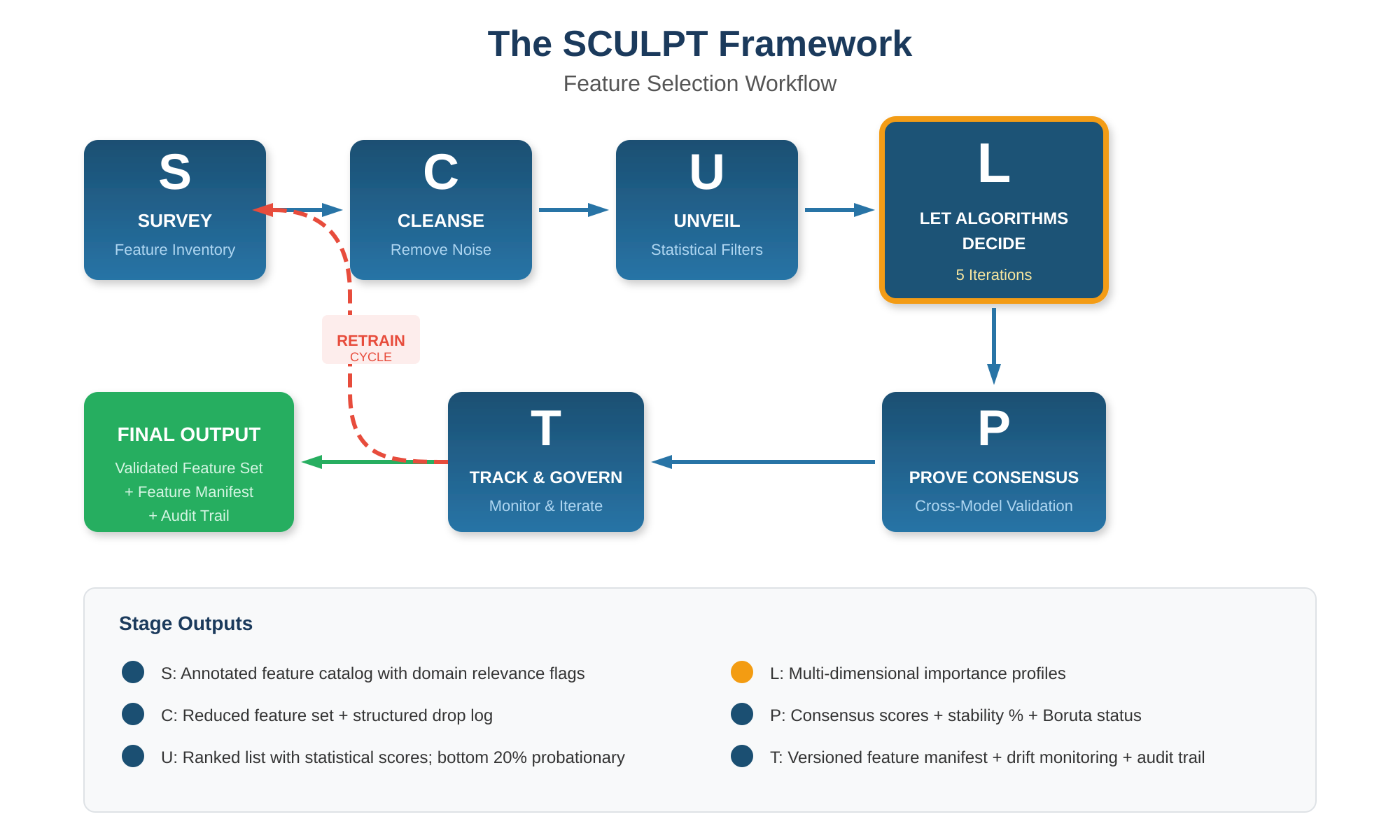

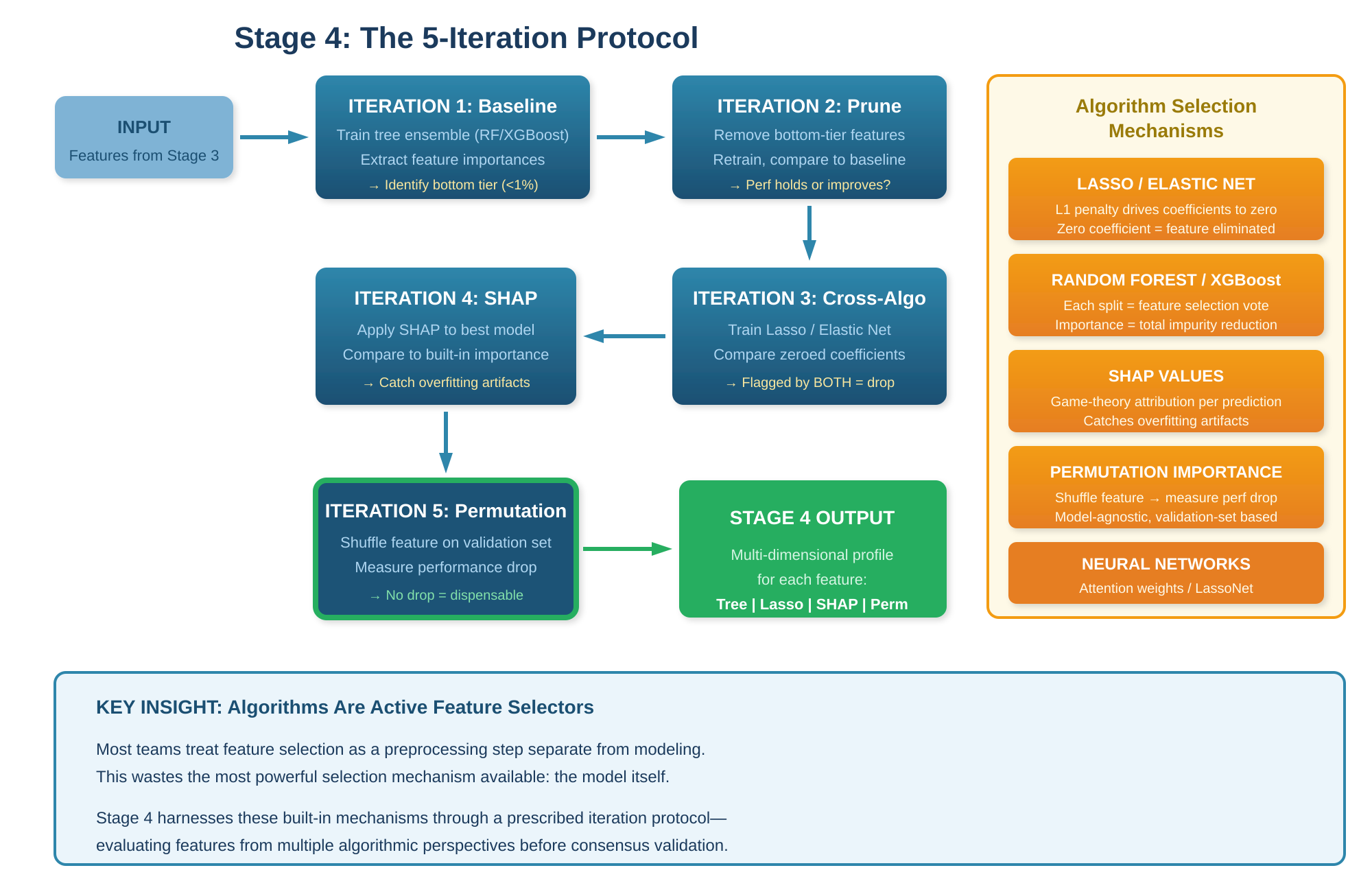

Stage 4: Let Algorithms Decide

This stage is the core differentiator of the SCULPT framework. Most treatments of feature selection position algorithmic methods as one category among several. SCULPT positions them as the primary mechanism—because the algorithms performing feature selection during training have access to information that no pre-model method can capture: the actual predictive relationship between features and the target, including interactions, nonlinearities, and context-dependent effects.

Figure 2: Stage 4 — The 5-Iteration Protocol and Algorithm Selection Mechanisms

The Mechanism: How Algorithms Select Features During Training

Every major ML algorithm family contains an inherent feature selection mechanism. Understanding these mechanisms is not academic background—it is operational knowledge required to use Stage 4 effectively.

Regularized Linear Models

Lasso regression (L1 regularization) adds a penalty proportional to the absolute value of each coefficient during optimization. As the regularization parameter increases, coefficients shrink—and some are driven exactly to zero. A zero coefficient is an algorithmic decision that the corresponding feature adds no value. The regularization path—the trajectory of all coefficients as the penalty increases—is itself a feature importance map. Features surviving at high penalty levels are the model’s highest-confidence selections.

Lasso’s known weakness is instability among correlated features: from a group of correlated variables, it arbitrarily retains one and zeros the rest, and the choice shifts across data samples. Elastic Net addresses this by combining L1 (sparsity) and L2 (grouping) penalties. With its mixing parameter between 0.5 and 0.8, Elastic Net tends to include or exclude correlated features as groups, producing more stable selections. Practitioners should observe how the selected set changes across mixing parameter values—features that are consistently selected are genuinely important; features that flicker in and out are sensitive to regularization assumptions.

Tree-Based Ensembles

Every split in a decision tree is a feature selection event: the algorithm evaluates all available features and selects the one that maximally reduces impurity (Gini for classification, MSE for regression). Random Forests aggregate this across hundreds of bootstrapped trees, each seeing random subsets of data and features. A feature that consistently ranks in top splits across 500 trees has earned its importance through preponderance of evidence.

Gradient boosting (XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost) adds a sequential dimension: each new tree learns from the residual errors of the previous ensemble, naturally concentrating on features that explain what existing trees get wrong. XGBoost’s gain metric—the average improvement in loss when a feature is used for splitting—is the most informative importance measure for feature selection, as it directly quantifies each feature’s contribution to predictive improvement.

The documented limitation of tree-based importance is bias toward high-cardinality and continuous features, which have more possible split points and thus more opportunities to appear useful. This bias is precisely why SCULPT requires multiple importance methods rather than relying on any single one.

Neural Network Selection Mechanisms

Deep learning models lack native feature importance in the tree sense, but three mechanisms serve as implicit selectors. Attention mechanisms assign learned weights to input features during training—consistently low weights indicate low relevance. Variational dropout at the input layer assigns learnable per-feature dropout probabilities, revealing which inputs the network can tolerate losing. Most directly, LassoNet applies L1 regularization to the network’s first layer, zeroing out irrelevant inputs while preserving the network’s capacity for nonlinear interaction capture among retained features.

Post-Hoc Attribution: SHAP and Permutation Importance

Two methods that operate on trained models provide critical cross-checks. SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) computes each feature’s contribution to each individual prediction using cooperative game theory, providing both per-prediction explanations and global importance rankings. Its value in SCULPT lies in catching features whose built-in importance is inflated by overfitting—a documented divergence between SHAP and impurity-based importance.

Permutation feature importance shuffles each feature independently on the validation set and measures the resulting performance drop. Features causing no performance loss when shuffled are genuinely dispensable. This method is model-agnostic and operates on held-out data, making it the most direct measure of a feature’s real-world utility. The main caveat—that correlated features mask each other’s permutation effect—is mitigated by Stage 2’s correlation cleanup.

The Prescribed Iteration Protocol

The power of algorithmic selection emerges across iterations, not in a single pass. SCULPT prescribes five iterations:

Iteration 1 — Baseline: Train a tree ensemble (Random Forest or XGBoost) on all features surviving Stage 3. Extract importance rankings. Identify features contributing <1% of total importance as the bottom tier. Record baseline performance metrics.

Iteration 2 — Pruning: Remove bottom-tier features. Retrain the same model. Compare performance to baseline. If performance holds or improves, the removal is validated. If it degrades meaningfully (>1–2% on the primary metric), selectively reintroduce features nearest the cutoff.

Iteration 3 — Cross-algorithm validation: Train a Lasso or Elastic Net on the same feature set. Compare zeroed-out features with the tree model’s bottom tier. Features flagged as unimportant by both a linear model and a tree model have a strong case for permanent removal. Disagreements warrant investigation—they often point to nonlinear relationships or correlated-group handling differences.

Iteration 4 — SHAP analysis: Apply SHAP to the best-performing model. Use global SHAP importance (average absolute SHAP value) as a cross-check against built-in importance. Features with high built-in importance but low SHAP importance may be overfitting artifacts. Features where SHAP and built-in metrics agree are high-confidence selections.

Iteration 5 — Permutation reality check: Apply permutation importance on the validation set. Features whose permutation causes zero performance loss are confirmed dispensable. This is the final, model-agnostic, held-out-data test before features enter the consensus stage.

After five iterations, each surviving feature has a multi-dimensional importance profile—tree importance, regularization survival, SHAP attribution, and permutation impact. This profile, not any single score, informs the consensus decision in Stage 5.

Stage 5: Prove Through Cross-Model Consensus

Every algorithm carries inductive biases that affect its feature preferences. Trees favor features with many split points. Linear models favor clean linear relationships. Neural networks can exploit interaction structures invisible to simpler models. Relying on one model’s rankings does not measure feature importance—it measures that model’s biases.

SCULPT’s consensus protocol requires training at least three fundamentally different model families on the surviving feature set and computing a weighted consensus score: the number of families ranking a feature in their top-N, weighted by each family’s validation performance. Features appearing across all families are consensus features—robust and algorithm-independent.

Bootstrap stability analysis then tests whether consensus holds across data variation. The full pipeline (Stages 1–4) is run on 50–100 bootstrap samples. Features selected in 80%+ of runs are designated stable; those in fewer than 50% are unstable. The RENT methodology (Repeated Elastic Net Technique) provides a formalized implementation by training Elastic Net ensembles on distinct data subsets and evaluating weight distributions across all elementary models.

As a final validation layer, Boruta tests whether each real feature statistically outperforms its own randomized shadow copy within a Random Forest. Features that cannot beat their shadow are confirmed unimportant. This provides a statistical decision (confirmed, rejected, or tentative) rather than an arbitrary threshold.

Only features that pass consensus scoring, bootstrap stability testing, and Boruta confirmation survive to production deployment.

Stage 6: Track, Govern, and Iterate

Feature selection is not a one-time event. In production, data distributions drift, new features become available, and previously important features decay. Without governance, feature sets degrade silently.

SCULPT’s governance layer has four components. Feature importance drift monitoring flags any feature whose importance drops 30%+ across retrain cycles. A feature manifest—versioned alongside the model artifact—documents every feature, its source, selection rationale, and importance scores at the time of selection. A permanent drop decision audit trail logs every removed feature with the stage of removal, reason, threshold, and performance impact. Periodic re-evaluation (quarterly minimum for production models) re-runs the full SCULPT pipeline to detect decayed features and evaluate new candidates.

This governance layer is essential in regulated environments. FDA AI/ML guidance, OCC SR 11-7 in financial services, and emerging frameworks such as the EU AI Act all require documented, traceable model development decisions. The feature manifest and audit trail are what you present to an inspector, auditor, or review board when asked to justify the variables in your model.

Design Principles

Beneath the six stages, SCULPT embodies three principles that differentiate it from both academic taxonomies and ad-hoc industry practices.

Progressive refinement over one-shot selection. Features are evaluated through successively more sophisticated lenses—domain expertise, statistical independence, algorithmic training behavior, cross-model consensus, and production monitoring. Each lens catches what the previous ones missed. A single-method approach is blind to anything that method cannot detect.

Algorithms as active participants. Treating feature selection as a pre-processing step that precedes modeling wastes the most powerful selection mechanism available: the model itself. Lasso zeros coefficients. Trees vote at every split. Gradient boosting concentrates on residual-reducing features. Stage 4 deliberately harnesses these built-in mechanisms through a prescribed iteration protocol.

Governance as integral, not peripheral. The audit trail, feature manifests, and drift monitoring in Stage 6 are not add-ons. They are integral to the framework because accountability is integral to responsible ML deployment. The ability to explain every feature inclusion and exclusion decision, with evidence, is a non-negotiable requirement in any environment where AI decisions carry consequences.

The name captures the method: you are sculpting a precise, defensible feature space from raw data—progressively, iteratively, with documented intent. Each stage removes another layer of noise. What remains is signal.

Models built on a sculpted feature set are simpler, faster, more interpretable, and more stable in production. That is not a theoretical proposition. It is what two decades of building ML systems in regulated environments consistently demonstrates: the quality of the feature set determines the quality of the solution.

SCULPT provides the process to make that quality repeatable.

References

Breiman, L. (2001). Random Forests. Machine Learning, 45(1), 5–32.

Chen, T., & Guestrin, C. (2016). XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. ACM SIGKDD.

Fisher, A., Rudin, C., & Dominici, F. (2019). All Models are Wrong, but Many are Useful. JMLR, 20(177).

Guyon, I., & Elisseeff, A. (2003). An Introduction to Variable and Feature Selection. JMLR, 3, 1157–1182.

Jenul, A., et al. (2021). RENT — Repeated Elastic Net Technique for Feature Selection. arXiv:2009.12780.

Kursa, M. B., & Rudnicki, W. R. (2010). Feature Selection with the Boruta Package. J. Stat. Software, 36(11).

Lemhadri, I., et al. (2021). LassoNet: A Neural Network with Feature Sparsity. JMLR, 22(127).

Lundberg, S. M., & Lee, S.-I. (2017). A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. NeurIPS 30.

Tibshirani, R. (1996). Regression Shrinkage and Selection via the Lasso. JRSSB, 58(1), 267–288.