A fundamentally simple concept of MVP (Minimum Viable Product) often in practice gets intermingled with our personal experiences; knowledgebase; perceptions; beliefs; biases; the way we think things should work; organizational dynamics; politics, and or other influences. Because of this the concept of MVP no longer bears any resemblance to the real purpose of it. We unknowingly end-up creating complexities around the idea of an MVP that’s otherwise pretty straightforward and simple.

As a rule of thumb –

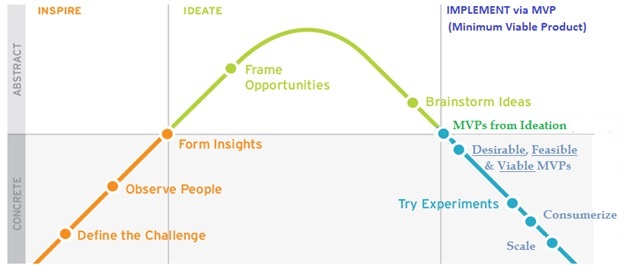

MVP is NOT a Destination it’s an Evolutionary Process – The MVP, minimum viable product or more appropriately minimum valuable product, is not a destination instead it’s a process. MVP is an iteratively built and consumerized solution that’s Desirable; Feasible, and Viable and is conceptualized through the cross-pollination of Design, Lean, and Agile practices. If this spirit of MVP is understood and followed correctly, it’s a fantastic opportunity to have a first-hand experience at how entrepreneurs build new products with minimal resources and why customers line up to pay for the value.

An MVP intends to deliver incremental value through optimized iterations of the Action -> Effect ->Feedback loop. This process is repeated until entire product is ready (assuming that any product is ever “finished”).

Though the ultimate goal is to meet customers need, all too often we lock ourselves into some intermediary non-value add requirements that tie our hands and stops us from moving forward— all in the name of “creating an MVP.” By doing so, we damage the real purpose of an MVP. An MVP is not the straightest line from idea to execution — it’s the first step in an evolutionary process that starts with the MVP and builds over time into the “full” product that your customer needs.

Also, too often we start engaging in discussions about MVP, especially outside of the MVP core team (the customer is always part of the core team). When that happens, we find ourselves being challenged to broaden the capabilities, to add features and functionality, and to solve more problems than we should with the first iteration of our efforts. When we do this, we are no longer building an MVP, but instead embarking on something that’s much bigger. The more you add to your MVP, the further away you’re going to get from being able to prove or disprove your hypothesis (covered in next paragraph) reliably, and the more time it’s going to take to deliver. To build an MVP that’s genuinely an MVP requires an intense amount of discipline from the product manager and the team working on it. Within the right context of an MVP, the product manager or anyone in charge of the successful delivery of value to the customer should challenge every new addition of features.

It’s all about proving or disproving Assumptions established via Business-Value Hypothesis – The use of MVP as a vehicle for value delivery is built on the premise that our success on anything is as good as the validity of our assumptions. Sooner we can prove or disprove our assumptions better our chances become at succeeding. Any assumption can be expressed via hypothesis, and in case of MVPs in a mature and established organization, it’s represented via business-value hypothesis that we need to prove or disprove. In fact, while executing on an MVP, if we ever find ourselves unable to move forward or decide on next course of actions then refocus on the business value hypothesis, we are guaranteed to find an answer.

In fact, the business-value hypothesis is the link to write user stories/ epics as in scrum development – a methodology usually applied towards MVP implementation. Unless we have value-hypothesis defined nothing we build will matter, and we will remain disconnected from the reality.

With a real business problem as a motivator, there are four primary attributes to business-value hypothesis associated with an MVP –

CUSTOMER

VALUE

SOLUTION (what problem this MVP is solving and how)

SUCCESS CRITERIA

The business-value hypothesis is then expressed as –

We believe that <this capability (SOLUTION)> will result in <this outcome (VALUE)> for <this (CUSTOMER)> we will know we have succeeded when <we see a measurable signal (SUCCESS CRITERIA)>

To prove or disprove above value-hypothesis, we then establish sets of user stories for the core business-value hypothesis and then find ways to prove or disprove hypothesis associated with a set of user-stories. A collection of user stories is one MVP.

“If a set of first user-stories are proven after the first iteration of development then that implies an MVP has delivered on its first promise and it meets customers’ expectations, now let’s move on to proving next set of user-stories OR the solution delivered is good enough, and we can stop.”

BUT

“If a set of first user-stories are not proven after the first iteration then that implies an MVP has failed to deliver on its first promise and we need to reestablish the business-value hypothesis. At this point, we can either decide to stop working on an MVP or go back to re-understanding the customer need and realigning Customer, Value, Solution (MVP), and or Success Criteria.”

When we try to define and build an MVP that’s not focused on testing a hypothesis, we lose our focus and with that loss of focus comes almost inevitable scope creep. If we can continually point to the hypothesis that we’re trying to test, and challenge incoming requests against that goal, we gain the discipline that we need to build a Minimum Viable Product and not just some small set of features that are spread out among different purposes.

Think Frugal – Any solution that’s not the Minimum is NOT an MVP

Ask yourself a simple question – “If my hard earned very-limited personal money is on the line, and there is an absolute need to buy something for my family or someone I care about, what would I do? How would I juggle other demands to fit this particular need? Can I postpone my purchase without compromising on my family’s immediate needs? It’s challenging to bring this personal perspective to our jobs, but we will be surprised that many of our answers lie in these simple personal perspectives. Thinking frugal should enable required discipline and creativity to stay lean and agile, towards incremental value delivery.

Read “Jugaad – An act of Frugal Innovation.”

The concept of an MVP is as revolutionary as it’s evolutionary. It is also an opportunity to be an apprentice and learn how an entrepreneur thinks or an intrapreneur in a mature organization should think and act towards enabling exponential transformations.

As you execute on more MVPs, you will realize that you are creating unbelievable capabilities for your organization and yourselves in future skills that are going to be in high demand. You will also recognize that every failure, within the right spirit of innovation with MVP as a vehicle for value delivery, is leading you to guaranteed successes in many other areas.

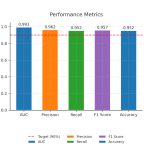

A successful MVP (or any solution), when looked at from the innovation management lenses should have the following journey –

Ref: IDEO + ExperiencePoint: Design Thinking Innovation Process